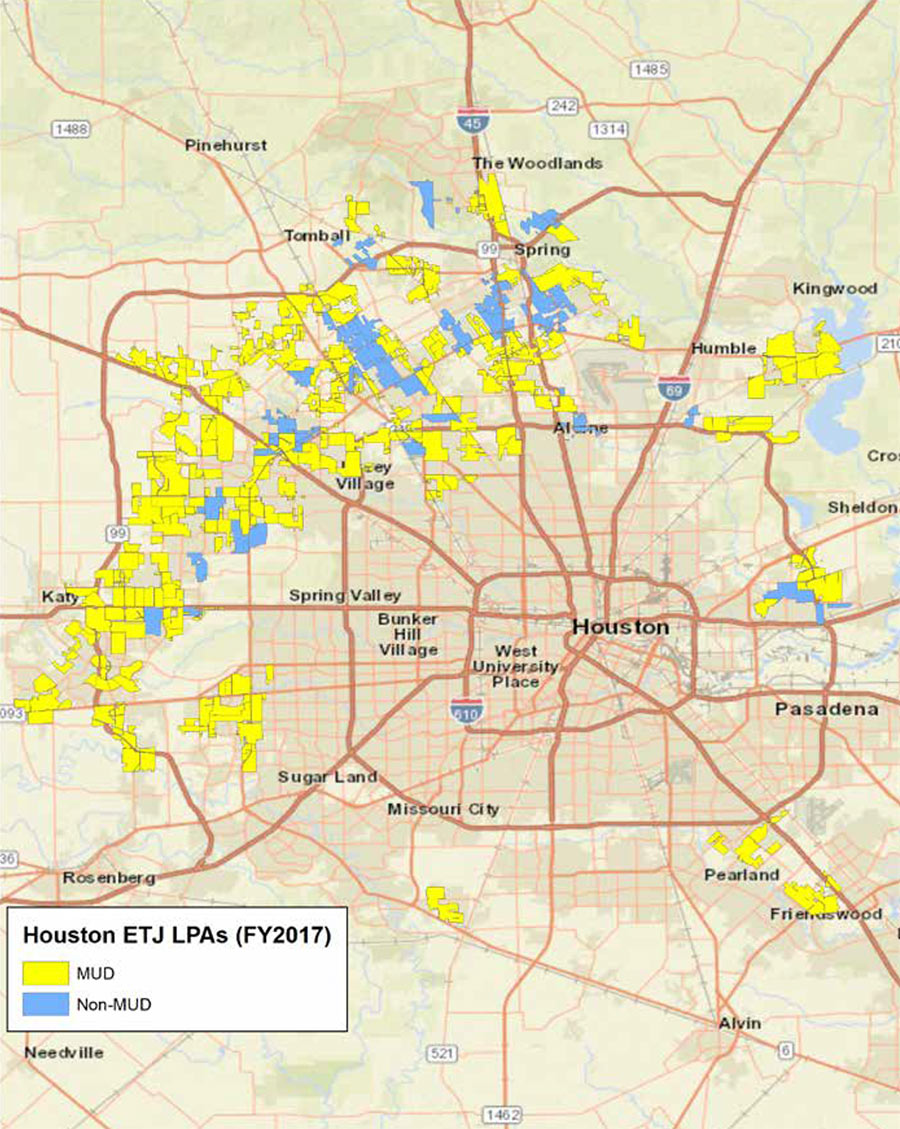

Since 1995, a new kind of land designation has been cropping up all along Houston’s outskirts: the LPA, or limited-purpose annexation. It’s a way for the city to collect sales tax in small, usually commercial, portions of unincorporated areas without formally annexing them or providing them with city services. Often LPAs are established inside an existing MUD (as shown above in yellow), although they doesn’t have to be (as shown by the blue). “The pursuit of these agreements is often framed by the city as a commuter tax,” according to a recent report from Rice’s Kinder Institute, “aimed at collecting revenue from residents who live outside of Houston but who use the services provided by the city.”

But there’s another reason why more than 200 LPAs now encircle the city, mainly between Hwy. 6 and the Grand Pkwy. Last year, the Texas legislature passed a bill that limits cities’ annexation power by allowing the communities they want to annex to hold their own referenda before their extra-territorial turf can be snatched up. One exception: A referendum isn’t necessary if the city and the area to be annexed have a preexisting agreement that says so. Many of Houston’s LPAs include this carve-out, meaning that when they expire — the typical term is 30 years — the areas they regulate will be up for grabs by the city . . . no local vote needed.

***

Until that happens, LPAs remain a money-maker for Houston, bringing in $106.6 million in sales tax over the 2017 financial year. When the LPA is situated inside an existing MUD, that revenue is often split 50-50 between the city and the district. And in many cases, the 2 jurisdictions opt to switch up their tax rates over time, helping to bring the numbers in line prior to annexation.

- Governing a Growing Region (PDF) [Kinder Institute for Urban Research]

Map: Kinder Institute for Urban Research

I tell ya, it’s almost like Texas’ system of local governance is designed to be terrible and convoluted. Almost.

These areas don’t get ANY city services, and don’t get any voting power with respect to how the money the city collects is spent. Blatant cash grabbing from a city that has proven it has little to no fiscal responsibility.

The city is going to have to annex to pay for Prop B and everything else.

The way the local governance works is really screwed up.

– Texas cities have extraterritorial jurisdiction which gives them rules in zoning even in areas where they don’t tax or provide services to.

– Cities can only expand in a given a percent of how big they are, meaning they can expand more and more every year

– If you’re in extraterritorial jurisdiction and want to incorporate, it requires permission of the host city

– The city usually expands more to pay for the services of the newly expanded area

– Even in annexed areas, the cities don’t have to provide things like sewage for years afterward

This happened in Wellborn back in 2011, where the “citizens” of Wellborn wanted to incorporate to avoid being annexed by College Station, but the city council (unelected by Wellborn, of course, since they were outside the city limit) was the one on whether to incorporate, meaning that functionally everything was in the city’s favor.

The key metric cities should look at when expanding territory is the amount of new tax generated, divided by the cost to service the new development, including the full life-cycle cost (including eventual replacement) of the associated infrastructure. For most territorial expansions, this number is much less than 1.0, which means that, over a sufficiently long horizon, the new territory costs more than it brings in.

However, over a short enough time window, say the typical term of office of a mayor or council member, the extra tax revenue can help pay current bills, leaving the future cost to a future mayor.

If cities look at the actual full life-cycle costs and benefits of new development, they will almost always prefer infill and densification over sprawl and annexation.