How’s this for a twisting story line? An architect commissions a famous artist to create a site-specific drawing in a house he has built for himself. The artist, who never touches his own works, creates exacting instructions that installation artists follow to create the 30-ft.-tall artwork in the living room of the home. The artist dies. A few years later, the architect dies, offering his home and the majority of his extensive art collection to a local but world-famous museum of which he was a trustee. The museum decides to sell the home and add much of the art to its collection, but there’s a problem with the wall drawing. It can’t be moved, and the museum is stymied by a restriction: It is not allowed to sell any artwork that has been bequeathed to it.

Here’s where the plot — and the drywall mud — thickens: the museum, unable to remove the artwork from the home without destroying it, comes up with an alternative plan. It will plaster over the drawing, rendering it unrecoverable.

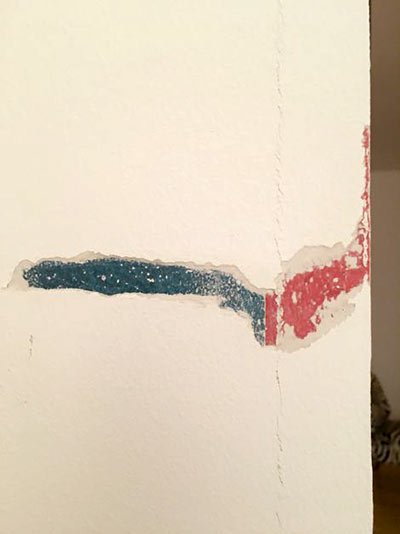

Years later, the purchaser of the home is telling this story to a houseguest — who in a fit of curiosity grabs a dull knife and starts chipping away at the wall. The white coating flakes off. To his and his host’s surprise, a tableau of blue, red, and yellow appears: a fragment of the original drawing underneath.

What is this? The first 20 minutes of a new Wes Anderson movie, an episode of Columbo, or the setup for a Siri Hustvedt novel? No, its just the state of play at 1202 Milford St. in the Museum District. The artist is Sol LeWitt. The museum is the Menil Collection. The home is the former residence of Houston architect Bill Stern. And the plotline is still in progress:

***

The original work was created directly on the surface of the wall using multiple layers of ink applied with a cotton cloth. Although the Menil covered over the drawing, it did accept the instructions for how to make it into its collection.

Stern’s home is pictured below. As an architect, he also led the renovations of the Menils’ own River Oaks home, as well as that of the Contemporary Arts Museum.

Inside, the zombie LeWitt drawing is making its presence known along a jagged line cut into the wall. You can see it behind the piano and under the more recently hung artwork on the living room wall in this photo of the interior of the home, which now serves as the residence of a Houston dentist:

So what happens next, and how can we follow the continuing butter knife action? “This will be the story of Unerasing a Sol LeWitt,” reads a website set up to document the unauthorized exhumation of the work. It promises “More to come.” There are also Twitter and Instagram feeds for the project.

- Un-erasing Sol LeWitt

- Houston architect’s towering Sol LeWitt installation is a piece of American art history [CultureMap]

- Previously on Swamplot:Â Menil Collection Taking Bill Stern’s Art, but Trying To Sell His Museum District House for $1.475 Million;Â William F. Stern, 1947—2013

Photos: Stern and Bucek Architects/Hester + Hardaway (living room, exterior); Un-erasing Sol LeWitt (line drawing fragments); Tyler Rudick (Bill Stern)

Okay, that’s a pretty damn cool story.

Yes, very cool.

Also: i think i need to change careers and become a dentist.

Amazing!!!

So the museum covered up the art because it believed that the art would prevent the sale of the home? Am I understanding that correctly? I sure do hope that there is more to the story, because otherwise the museum should be really embarrassed by this. Restraints on the alienation of real property are not enforceable. There was no need to destroy the art.

@Insider, Agreed, there has to be more to this story of why the art was obscured.

It’d be (ahem) revealing to know who owns the r&r on the artwork. Is it with the LeWitt Estate heirs? Did the Menil manage to obtain them? (maybe) Regardless, obviously whoever currently has the rights doesn’t have possession of the artwork, which makes it difficult to protect said rights against infringement. And, as the Menil already discovered, the work isn’t moveable without serious harm. So, how do you tell a potential owner of the house, yeah you have an original Sol LeWitt on your wall but it isn’t actually yours so you can’t photograph it, remove or change it in any way, and don’t even think of selling mugs, t-shirts, posters, etc. of the thing. Btw, keep the interior climate to certain standards so the work suffers no damage. And working out who would pay for security and fine arts insurance (not to mention exactly how) is a whole ‘nother migraine. Stern probably thought the Menil would keep the house in perpetuity, the Menil not so much. Uninformed guess would be that the curatorial decision was made that the artwork wasn’t a LeWitt masterpiece worth the money and effort to find a more elegant solution than just plastering over the now abandoned art. Wonder if the Menil will pull a cease and desist order on the uncovering project.

But, yep, it’s a great story.

Most think his “art†was awful, I don’t blame them covering it up. John Singer Sargent was great artist. I’ve seen Kindergartners that were better painters than this “artistâ€. We can all scribble on a wall. Moving on

@Insider: I read this to say the museum covered up the artwork TO sell the house. The museum was prevented from selling the artwork. By covering the artwork, it could argue it sold the house without consideration for the artwork. Maybe Swamplot can confirm…

Please reread the story … the reason the art was covered up was a legal issue. The mural could not be sold as art, but the museum couldn’t move it without destroying it. The solution was to cover it with plaster (an age old tradition of “removing” unwanted murals) which made it possible to sell the house without breaking their restrictions on selling bequeathed artwork.

Let’s hope that professional restorers can work their magic …

Maybe it’s one of those “If we can’t have it, neither can anyone else.” scenarios?

@ Insider and TimP: the original art was covered before the house was sold because according to the terms of the bequest to the Menil Collection, they could not sell any of the artwork that was given to them. Since the Menil could not reasonably remove a wall from the house, the artwork was covered over so that when the house sold, the museum was within the boundaries of the bequest. Understand now?

Well by making the artwork unrecoverable, The Menil would no longer need to maintain or insure the work…

Very cool. And the metronome is a nice touch.

“John Singer Sergeant”… wow, now if I ever luck into possession of a River Oaks/Courtlandt/North Blvd home I’ll know where to source the “random paintings of old upper crust people” that are de riguer for such a dwelling. Thanks, Jonathan!

Assume that the art was never covered up. If the museum wanted to sell the home, with the art still intact, no court would ever hold that the sale of the home constituted a sale of art in violation of Stern’s wishes. And even if a court were inclined to construe the sale of the home as the sale of art, the court could not give effect to Stern’s wishes by preventing the sale because restraints on alienation are void for being against public policy. Which would mean that there was no legal justification for destroying the art. The museum could have sold the home with the art on full display because the home and the art were one and the same. That was my point.

I always thought that bequests with “no sale” clauses were anathema to non-profits. Is this part of the Menil charter or something? If so, why don’t the trustees take it to court? That said, they probably really wanted the Stern collection and figured that painting over the mural to sell the house was not that big a deal.

@ShadyHeightster, Yes, I read the article and understand those points. Thanks for summarizing them, though.

@Insider, Thank you for expanding on these points. I suppose one can just accept the story on its face, but I agree with your perspective and still wonder if there’s a story behind the story.

What are the potential tax implications for the new homeowner?

“What are the potential tax implications for the new homeowner?”

.

In what way? If the house is worth a lot more due to the art, then the tax implication would be on any gain at sale. Depending on the timing of sale, it would be taxed as income or capital gains.

.

But if the house is worth $100000000 more due to the art there is no immediate tax implication. Any more so than if I bought a few baseball cards at a yard sale for $1 and one was worth $5k. Where my tax bill would come is if/when I realized that gain at sale.

Many years ago I worked as a cataloguer in the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. We had nearly the same issue with Sol LeWitt and Richard Long, both artists whose work is often site-specific and completely created (and re-created) by others. When Sol and Richard do…did do…commissions for museums, the standard policy is that when a work is gifted to the museum, the artist gives implicit instructions for the work to be executed. Sol gave the MCAC dozens of working drawings for a single work; the most important thing were colors, geometry, placement, etc. Richard did one in-person installation, then the museum took hundreds of photos, made drawings, etc. for perpetuity.

It’d seem to me that the homeowner should’ve received drawings from Sol, along with instructions for colors, and a legal document allowing for its removal/relocation. I worked with Mr. LeWitt briefly. He didn’t seem to have a problem with his work being re-created or moved around the museum, but he would’ve gone nuts knowing a museum signed-off on plastering over it. I also can’t see a place like the Menil Collection agreeing to destroy an artwork.

I’m pretty sure that Bill Stern did get the instructions and drawings from Sol LeWitt, and they were part of his bequest to the Menil. And without hearing otherwise, I’m pretty sure that it’s the Menil charter that prohibits selling donated artwork, not the terms of the Stern bequest. If so, that’s pretty unusual, isn’t it?

The author of this story calls this an “unauthorized exhumation” of the LeWitt work. Unauthorized? Why would a homeowner need to get anyone’s authorization to remove paint from a wall in a house they solely own? Is there really ANY possible legal issue here?