COULD HARRIS COUNTY SAVE UP SOME FLOODWATER FOR WHEN IT’S REALLY NEEDED?  Finding a way to stockpile floodwater during years of plenty, commissioner Jack Cagle tells Mihir Zaveri this week, might not only help to make more water available for use during Houston’s drought years. It might also be a way to check the Houston region’s tendency for subsidence (that slow, permanent sinking that can happen when groundwater is pulled out of Houston’s soft clay layers too quickly). Or maybe, Zaveri adds, it could be used to help keep seawater from being sucked into aquifers as fresh water gets sucked out the other side — as long as doing so didn’t accidentally contaminate those same aquifers with junk from the surface. Who knows? Nobody, yet — but the county commissioners have given the $160,000 okay to a study team to shed light on whether it would be possible, feasible, or advisible for Harris County to pump floodwater underground for storage during major storms. [Houston Chronicle; previously on Swamplot] Photo of Meyerland flooding on Tax Day 2016: Tamara Fish

Finding a way to stockpile floodwater during years of plenty, commissioner Jack Cagle tells Mihir Zaveri this week, might not only help to make more water available for use during Houston’s drought years. It might also be a way to check the Houston region’s tendency for subsidence (that slow, permanent sinking that can happen when groundwater is pulled out of Houston’s soft clay layers too quickly). Or maybe, Zaveri adds, it could be used to help keep seawater from being sucked into aquifers as fresh water gets sucked out the other side — as long as doing so didn’t accidentally contaminate those same aquifers with junk from the surface. Who knows? Nobody, yet — but the county commissioners have given the $160,000 okay to a study team to shed light on whether it would be possible, feasible, or advisible for Harris County to pump floodwater underground for storage during major storms. [Houston Chronicle; previously on Swamplot] Photo of Meyerland flooding on Tax Day 2016: Tamara Fish

Tag: Groundwater

The field above, on the block between W. 24th, W. 25th, Ashland and Rutland streets in the Heights, will be the subject of a public meeting next month, a reader who got a letter about it from the city notes to Swamplot. The land (an also-ran in the Best Teardown category for the 2010 Swampies) was previously the site of some of National Flame & Forge’s operations, which extended into the double block immediately to the north (now sprouting the townhomes visible in the distance). The owners have spent some time in the last few years taking stock of some industrial leftovers on the property, and are now seeking a Municipal Settings Designation for the land, which will legally nix any future use of the site’s chromium-and-trichloroethylene-spiked groundwater for drinking purposes.

The letter, addressed to nearby property owners and water-well-havers, emphasizes that no city water sources are affected by the contamination, and adds that the city is also legally required to send the meeting invite to anyone who owns a water well within 5 miles of the site. The map below is included with the application from NFF Realty for the no-drinking label; the aerial shows the rough boundaries of areas where water sampling over 2014 and 2015 showed more-than-you-want-in-your-coffee levels of chromium (in red) and trichloroethylene (in yellow):

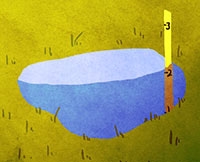

COMMENT OF THE DAY: WHAT COUNTS AS A SPRING IN HOUSTON  “The definition of a ‘spring’ can vary a lot, and is used loosely here.

In Harris County, where the topography is relatively flat, most of our ‘ponds’ and ‘lakes’ are either borrow pits (excavated to raise the grade elsewhere) or dammed-up gullies/ravines along existing bayous. In this case, it is the latter — a gully of Buffalo Bayou that was dammed up, then developed into a neighborhood.

A ‘spring’ is generally a point where the top groundwater table meets the surface. In our area, when we receive a lot of rain, the groundwater table can actually reach the surface. So a spring can range from a trickle of water to a puddle standing on the surface. When I dug the post holes in my backyard for my cedar fence, I hit groundwater at 2 feet deep because of recent heavy rain. In dryer periods, the water table drops, and springs continue to occur along steep cuts in the topography (either along a bayou that has eroded downward, or a man-made excavation). This is not what you find in the Hill Country, where large gaping holes in limestone spew thousands of gallons per hour, sometimes creating rivers out of nothing.

So effectively, any hole in Houston greater than 2 feet deep at some point will become ‘spring-fed.’ During the bad drought of the past few years, most likely the groundwater table dropped and stopped feeding this former gully of the bayou, and the ‘lake’ was most likely topped off by (1) automatic sprinkler runoff and (2) the small amount of storm water runoff they received, as the lake also serves as the neighborhood drainage ditch.” [Superdave, commenting on There’s a Tour of Texas and More in a Developer’s Lakefront Sandalwood Spread] Illustration: Lulu

“The definition of a ‘spring’ can vary a lot, and is used loosely here.

In Harris County, where the topography is relatively flat, most of our ‘ponds’ and ‘lakes’ are either borrow pits (excavated to raise the grade elsewhere) or dammed-up gullies/ravines along existing bayous. In this case, it is the latter — a gully of Buffalo Bayou that was dammed up, then developed into a neighborhood.

A ‘spring’ is generally a point where the top groundwater table meets the surface. In our area, when we receive a lot of rain, the groundwater table can actually reach the surface. So a spring can range from a trickle of water to a puddle standing on the surface. When I dug the post holes in my backyard for my cedar fence, I hit groundwater at 2 feet deep because of recent heavy rain. In dryer periods, the water table drops, and springs continue to occur along steep cuts in the topography (either along a bayou that has eroded downward, or a man-made excavation). This is not what you find in the Hill Country, where large gaping holes in limestone spew thousands of gallons per hour, sometimes creating rivers out of nothing.

So effectively, any hole in Houston greater than 2 feet deep at some point will become ‘spring-fed.’ During the bad drought of the past few years, most likely the groundwater table dropped and stopped feeding this former gully of the bayou, and the ‘lake’ was most likely topped off by (1) automatic sprinkler runoff and (2) the small amount of storm water runoff they received, as the lake also serves as the neighborhood drainage ditch.” [Superdave, commenting on There’s a Tour of Texas and More in a Developer’s Lakefront Sandalwood Spread] Illustration: Lulu

All it takes is a little subtraction! Say you’ve got 20 picocuries of cancer-friendly alpha radiation per liter in your drinking water. Well, there’s gotta be some margin of error in measuring it, right? Say, 6 picocuries per liter? Then just go ahead and subtract that number out (because you’ve gotta be optimistic about these things, you know, or it’ll kill you). Then . . . voilà ! Your level of those nasty little mutation-causing particles is now just 14 picocuries. And phew! what a relief! Because the EPA’s “maximum contaminant level” for alpha radiation happens to be 15 picocuries per liter, and those math wizards at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality have just saved your community’s water supply from receiving a violation notice! Slight problem: since 2000, the EPA has requested that states not use this little data-jiggering technique. But not to worry: TCEQ’s Linda Goodins, who oversees all drinking-water safety regulation for the state, doesn’t think the EPA’s request was an actual requirement. (Just to placate to those ever-meddling feds though, TCEQ discontinued its subtraction technique last year.)

One of the more fascinating EPA Superfund sites in the Houston area is a neighborhood off Jones Road just north of FM1960. Residents who had earlier appreciated how convenient it was to drop off their dry cleaning at nearby Bell Cleaners began to regret that benefit in 2002 when the TCEQ announced that the local drinking water was laced with nasty levels of dry-cleaning solvent tetrachloroethylene, or PCE.

That was bad. But now it’s even worse: These residents will now be prohibited from drilling their own wells to drink the local groundwater!

Coalition members said they recently learned Harris County officials would not allow anymore water wells to be drilled in the Jones Road Superfund site, which covers the Evergreen Woods and Edgewood Estates neighborhoods west of Jones Road and north of FM 1960, and some commercial properties east of Jones Road.

“We understand that Harris County is putting health concerns above everything else, but several residents out here believed they could drill another well into a deeper aquifer if they needed to, and now that is not an option,” said Jones Road Coalition board member Ron O’Farrell.

According to a Houston Chronicle story, only 124 out of approximately 400 neighborhood property owners signed up for a proposed pipeline to bring uncontaminated drinking water into the area. But now, after a Harris County order banning new wells—and the recent discovery of trace elements of vinyl chloride in existing residential wells—some residents are saying they want to re-open the signup period.

Why were they so reluctant to sign up for a supply of nontoxic water in the first place?

Coalition members said there are two primary reasons some residents are concerned about signing the agreement that would allow them to hook up to the water pipeline. One clause in that agreement requires residents to permanently cap their individually owned groundwater wells, and the other gives the state unlimited access to their property during the project and remediation effort.

“I would not mind paying a fee for the tap and paying a plumber, or whomever it takes, on my own to tap in to the pipeline as long as I don’t have to sign the agreement ad give them complete access to my land,” said Donald Haus, and Edgewood Estates resident.

- Jones Road coalition wants to reopen pipeline agreement [Houston Chronicle]

- Jones Road Groundwater Plume [TCEQ]

- Jones Road (Harris County) Texas (PDF Superfund update) [EPA]