COMMENT OF THE DAY: A QUICK ALLEN PARKVIEW VILLAGE RECAP FOR HOUSTON NEWCOMERS  “. . . Back in the 1920s, the 4th Ward was Houston’s version of Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance. Racist white city officials did not want a thriving African American community right next to a rapidly growing downtown and demolished a huge section of the community to build public housing (the decisive blow to the 4th ward would be extending the freeway through the community, effectively cutting it off from downtown). APV was designed by MacKie & Kamrath and was intended to be public housing. It ended up as all white housing for veterans. Eventually, African Americans moved in as whites moved out and headed to the suburbs. In the ’70s, as the City was booming again, City officials wanted to demolish APV as it, and much of the rest of the 4th ward, was falling into disrepair. Every single move after that was just controversy on top of controversy. The City was accused of moving Vietnamese immigrants into APV to dilute the number of African Americans who opposed demolition. Then, there was a big master plan project proposed to redevelop the entire area, a court case over demolition of APV and designation of APV and the Fourth Ward on the national register of historic places. In the end, more than half was demoed and replaced with new apartments in 2000. The original MacKie & Kamrath designed buildings are architecturally and historically significant. But, like the history of the 4th ward, Houston’s transient population knows very little about the trials and tribulations behind APV. So, it is an easy target to troll for hate on preservationists.” [Old School, commenting on Comment of the Day: An Alternative Plan for the Site Next to Allen Parkway Village] Illustration: Lulu

“. . . Back in the 1920s, the 4th Ward was Houston’s version of Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance. Racist white city officials did not want a thriving African American community right next to a rapidly growing downtown and demolished a huge section of the community to build public housing (the decisive blow to the 4th ward would be extending the freeway through the community, effectively cutting it off from downtown). APV was designed by MacKie & Kamrath and was intended to be public housing. It ended up as all white housing for veterans. Eventually, African Americans moved in as whites moved out and headed to the suburbs. In the ’70s, as the City was booming again, City officials wanted to demolish APV as it, and much of the rest of the 4th ward, was falling into disrepair. Every single move after that was just controversy on top of controversy. The City was accused of moving Vietnamese immigrants into APV to dilute the number of African Americans who opposed demolition. Then, there was a big master plan project proposed to redevelop the entire area, a court case over demolition of APV and designation of APV and the Fourth Ward on the national register of historic places. In the end, more than half was demoed and replaced with new apartments in 2000. The original MacKie & Kamrath designed buildings are architecturally and historically significant. But, like the history of the 4th ward, Houston’s transient population knows very little about the trials and tribulations behind APV. So, it is an easy target to troll for hate on preservationists.” [Old School, commenting on Comment of the Day: An Alternative Plan for the Site Next to Allen Parkway Village] Illustration: Lulu

Houston History

COMMENT OF THE DAY: THE LAST MESSAGE OF DOWNTOWN’S ENTOMBED WESTERN UNION BUILDING  “. . . Soon after I moved to Houston, I had money wired to me at this Western Union building (this would have been November of ’81). Didn’t make much of an impression on me. I think the façade had been stripped off, and the office itself was shabby.

I started work at HL&P in February of ’82, and our offices looked directly across the street to the construction site. The ‘big pour’ for the concrete foundation slab was quite an event. Starting very early on a Sunday morning, a seemingly endless parade of mixer trucks crept down Louisiana Street. Obviously, most of the block had been excavated, and the lot where Western Union sat (well, sits) was supported by a series of diagonal beams. After seeing the engineering required to save that lot, the lower ‘banking hall’ design for that side of the building makes sense.

While construction continued, the south side of the WU was given a fresh coat of paint with a large graphic proclaiming ‘A Gerald R. Hines Project‘ (or some such thing), which doubtlessly is still there, virtually unseen for 35 years.” [BigTex, commenting on Comment of the Day: Inside the Western Union Building Buried Inside the Bank of America Center Downtown] Photo of banking hall interior, looking toward the Western Union building’s south wall: Bank of America Center

“. . . Soon after I moved to Houston, I had money wired to me at this Western Union building (this would have been November of ’81). Didn’t make much of an impression on me. I think the façade had been stripped off, and the office itself was shabby.

I started work at HL&P in February of ’82, and our offices looked directly across the street to the construction site. The ‘big pour’ for the concrete foundation slab was quite an event. Starting very early on a Sunday morning, a seemingly endless parade of mixer trucks crept down Louisiana Street. Obviously, most of the block had been excavated, and the lot where Western Union sat (well, sits) was supported by a series of diagonal beams. After seeing the engineering required to save that lot, the lower ‘banking hall’ design for that side of the building makes sense.

While construction continued, the south side of the WU was given a fresh coat of paint with a large graphic proclaiming ‘A Gerald R. Hines Project‘ (or some such thing), which doubtlessly is still there, virtually unseen for 35 years.” [BigTex, commenting on Comment of the Day: Inside the Western Union Building Buried Inside the Bank of America Center Downtown] Photo of banking hall interior, looking toward the Western Union building’s south wall: Bank of America Center

COMMENT OF THE DAY: INSIDE THE WESTERN UNION BUILDING BURIED INSIDE THE BANK OF AMERICA CENTER DOWNTOWN  “The Western Union building is only 2 stories. It is completely intact, tar and gravel roof included. The 3rd floor Mezzanine of the BOA building was built clear span over the top of the old WU building. The windows you see on the outside are for the mezzanine. As for the ‘gap’ between the buildings, you can walk/crawl around most of it. Some areas between the buildings are big enough that you could set a desk in there, some are tight enough to induce panic. There is basically nothing left from WU in there, but there were still some curious old artifacts last time I was in there. I worked for the building for a while, and led a few of the tours of architects/designers when this project was in the concept phase.” [ProFixer, commenting on For Its Next Trick, Bank of America Center Will Completely Digest the Secret Building It Swallowed 35 Years Ago] Photo: Mary Ann Sullivan

“The Western Union building is only 2 stories. It is completely intact, tar and gravel roof included. The 3rd floor Mezzanine of the BOA building was built clear span over the top of the old WU building. The windows you see on the outside are for the mezzanine. As for the ‘gap’ between the buildings, you can walk/crawl around most of it. Some areas between the buildings are big enough that you could set a desk in there, some are tight enough to induce panic. There is basically nothing left from WU in there, but there were still some curious old artifacts last time I was in there. I worked for the building for a while, and led a few of the tours of architects/designers when this project was in the concept phase.” [ProFixer, commenting on For Its Next Trick, Bank of America Center Will Completely Digest the Secret Building It Swallowed 35 Years Ago] Photo: Mary Ann Sullivan

Something you might not have noticed about Houston’s iconic Bank of America Center (top) at 700 Louisiana St. Downtown: There’s an entire unused building hidden inside. The thrice-renamed spiky Dutch-ish PoMo tower complex, designed by architect Philip Johnson in 1982, sits across the street from his other famous Downtown Houston office building, Pennzoil Place. It’s not obvious from the exterior or interior, but the 2-story former Western Union building on the corner of Louisiana and Capitol streets (pictured above in a photo from 1957) takes up almost a quarter of the block Bank of America Center sits on. This was Western Union’s longtime regional switching center; Johnson was asked to design his building around it because the cable and electrical connections maintained within it were deemed cost-prohibitive to relocate.

Something you might not have noticed about Houston’s iconic Bank of America Center (top) at 700 Louisiana St. Downtown: There’s an entire unused building hidden inside. The thrice-renamed spiky Dutch-ish PoMo tower complex, designed by architect Philip Johnson in 1982, sits across the street from his other famous Downtown Houston office building, Pennzoil Place. It’s not obvious from the exterior or interior, but the 2-story former Western Union building on the corner of Louisiana and Capitol streets (pictured above in a photo from 1957) takes up almost a quarter of the block Bank of America Center sits on. This was Western Union’s longtime regional switching center; Johnson was asked to design his building around it because the cable and electrical connections maintained within it were deemed cost-prohibitive to relocate.

Thirty-five years later, it’s the building’s anchor tenant that’s relocating: Bank of America, which now occupies 165,000 sq. ft., will move to Skanska’s Capitol Tower in a couple years. As part of a new set of renovations to the structure the bank is leaving behind, owner M-M Properties plans to completely dismantle what remains of the Western Union building, recapturing 35,000 sq. ft. of space without expanding the building’s footprint. Among the plans for the resulting space: A “reconfiguration” of the lobby and the addition of a “white tablecloth restaurant.”

The secret Western Union void is well disguised. It isn’t in the lobby of the 56-story tower but in the 12-story adjacent bank-lobby building fronting Louisiana St., more formally known as the the Banking Hall when the building first opened in 1983 as RepublicBank Center. It takes up the entire northern half of that structure: It’s beyond the colonnaded-but-blank wall on your right as you enter the lobby from Louisiana (on the left in this photo):

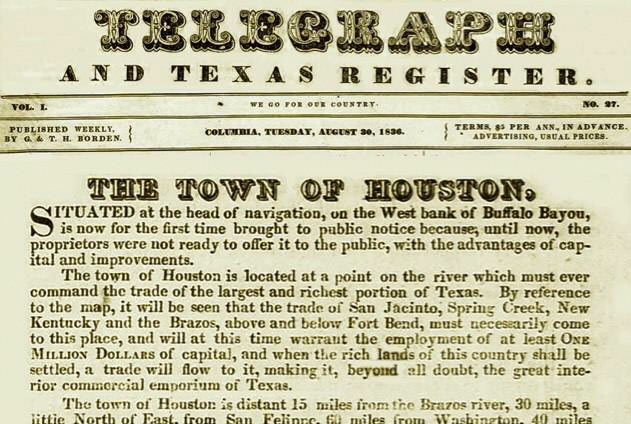

HAPPY BELATED BIRTHDAY, HOUSTON, YOU LOVABLE, MISIDENTIFIED SWAMP  Possibly overlooked amid the Harvey hubbub: Yesterday was the City of Houston’s 181st birthday — or more accurately, the 181st anniversary of the launch of an advertising campaign announcing its establishment, pursued by the soon-to-be-city’s founding real-estate hucksters. “It is handsome and beautifully elevated,” the Allen Brothers wrote of the Houston they imagined in that ad, “salubrious and well watered, and now in the very heart or centre of population, and will be so for a length of time to come.” [Previously on Swamplot] Image: Houstorian

Possibly overlooked amid the Harvey hubbub: Yesterday was the City of Houston’s 181st birthday — or more accurately, the 181st anniversary of the launch of an advertising campaign announcing its establishment, pursued by the soon-to-be-city’s founding real-estate hucksters. “It is handsome and beautifully elevated,” the Allen Brothers wrote of the Houston they imagined in that ad, “salubrious and well watered, and now in the very heart or centre of population, and will be so for a length of time to come.” [Previously on Swamplot] Image: Houstorian

Interested in a bit of booty plundered from the the birthplace of Bootylicious? The former Rice Mansion at 1505 Hadley St. in Midtown most recently served as the headquarters of Mathew Knowles’ Music World Entertainment and moonlighted as a wedding and event venue. According to Architectural Digest, Destiny’s Child recorded Bootylicious, as well as several other of its hit songs, inside this building. But Knowles sold the entire block bounded by Hadley, Crawford, Webster, and LaBranch streets late last year, and its new owner — Group 1 Automotive, the parent company of the neighboring Midtown Advantage BMW car dealership — has begun demolishing the structures sitting on it one by one.

Interested in a bit of booty plundered from the the birthplace of Bootylicious? The former Rice Mansion at 1505 Hadley St. in Midtown most recently served as the headquarters of Mathew Knowles’ Music World Entertainment and moonlighted as a wedding and event venue. According to Architectural Digest, Destiny’s Child recorded Bootylicious, as well as several other of its hit songs, inside this building. But Knowles sold the entire block bounded by Hadley, Crawford, Webster, and LaBranch streets late last year, and its new owner — Group 1 Automotive, the parent company of the neighboring Midtown Advantage BMW car dealership — has begun demolishing the structures sitting on it one by one.

For now, the Rice Mansion — minus a bunch of salvaged parts and furnishings, which were yanked out recently — is still standing. But some of its parts have already been spotted by a Swamplot reader on an internet auction site. Though the building is more than a century old, the offered materials are clearly of far more recent vintage. Behold:

COMMENT OF THE DAY: STATUES OF LIMITATIONS  “There’s a theory that says the important thing the person is known/celebrated for should determine whether a statue stays or goes (i.e., “describe this person in 50 words or lessâ€). George Washington is not known for fighting a war with his own country-people to own slaves, but as a founding member of our country. Though he was a slave owner, it was the practice at the time. Contrast with the Confederate leaders, who rose to prominence as fighters for a practice that was known to be evil. If there are Confederate leaders who are also known for something that is to be celebrated (such as putting Lee in front of an orphanage he founded), then there’s a strong argument for keeping that statue. Otherwise it’s merely Lost Cause glorification, which isn’t historically accurate, and with most of these statues, completely out of context (e.g., middle of a park, usually reserved for someone who deserves high praise).” [travelguy, commenting on The Great Texas Confederate Statue Roundup] Photo of monument to Confederate Lieutenant, Houston saloon owner, and gas-lighting and firefighting pioneer Dick Dowling in Hermann Park: Edward T. Cotham, Jr.

“There’s a theory that says the important thing the person is known/celebrated for should determine whether a statue stays or goes (i.e., “describe this person in 50 words or lessâ€). George Washington is not known for fighting a war with his own country-people to own slaves, but as a founding member of our country. Though he was a slave owner, it was the practice at the time. Contrast with the Confederate leaders, who rose to prominence as fighters for a practice that was known to be evil. If there are Confederate leaders who are also known for something that is to be celebrated (such as putting Lee in front of an orphanage he founded), then there’s a strong argument for keeping that statue. Otherwise it’s merely Lost Cause glorification, which isn’t historically accurate, and with most of these statues, completely out of context (e.g., middle of a park, usually reserved for someone who deserves high praise).” [travelguy, commenting on The Great Texas Confederate Statue Roundup] Photo of monument to Confederate Lieutenant, Houston saloon owner, and gas-lighting and firefighting pioneer Dick Dowling in Hermann Park: Edward T. Cotham, Jr.

A section of John Nova Lomax’s new Texas Monthly essay on Montrose’s continuing “it was better in the old days” rap chronicles a sequence of prominent changes to the neighborhood from the last decade. That it’s possible to find at least one Swamplot story corresponding to each noted example speaks to the longterm vigilance of this site’s tipsters — if not the author’s research methods. (Lomax in fact wrote a few of our stories himself; he’s a former Swamplot contributor and editor.)

Here’s the passage, altered by a peppering with Swamplot links to provide an annotated and illustrated version of Montrose’s recent journey from former counterculture haven to . . . uh, former counterculture haven:

THE DEATH, LIFE, AND CONTINUING OBITUARY OF MONTROSE, STILL TEXAS’S ‘COOLEST NEIGHBORHOOD’  Nostalgia for Montrose’s good old days as a counterculture hub has a history almost as long and involved as the neighborhood itself, curator of Houston lore John Nova Lomax points out in a new essay for Texas Monthly. “I’ve heard generations of these death-by-gentrification declarations. Hippies might tell you it died around the time Space City! went under in 1972,” he writes (Lomax himself was “conceived in Montrose by hippie parents, in a house on the corner of Dunlavy and West Alabama.”) “There have almost always been laments about rising rents: In 1973, Montrose was featured in Texas Monthly’s third-ever issue, with folk singer Don Sanders fretting about a mass exodus of creative types brought on when area leases topped a whopping $100.” Since then, however, the losses have only mounted: “Gentility has encroached on Montrose from the snooty, River Oaks-lite Upper Kirby district to the west, while Midtown’s party-hearty bros have invaded from the east and north. Property taxes and rents have both skyrocketed; despite the oil downturn, it’s almost impossible to find a one-bedroom for less than $800 a month. Having gained more acceptance from society at large, the LGBT community has scattered to neighborhoods like Westbury and Oak Forest. Bohemians have fled to the East End, Acres Homes, and Independence Heights — the gentrified Houston Heights no longer an option — or have left Houston altogether.” [Texas Monthly] Photo of house across from Menil Park, 1999: Alex Steffler, via Swamplot Flickr Pool [license]

Nostalgia for Montrose’s good old days as a counterculture hub has a history almost as long and involved as the neighborhood itself, curator of Houston lore John Nova Lomax points out in a new essay for Texas Monthly. “I’ve heard generations of these death-by-gentrification declarations. Hippies might tell you it died around the time Space City! went under in 1972,” he writes (Lomax himself was “conceived in Montrose by hippie parents, in a house on the corner of Dunlavy and West Alabama.”) “There have almost always been laments about rising rents: In 1973, Montrose was featured in Texas Monthly’s third-ever issue, with folk singer Don Sanders fretting about a mass exodus of creative types brought on when area leases topped a whopping $100.” Since then, however, the losses have only mounted: “Gentility has encroached on Montrose from the snooty, River Oaks-lite Upper Kirby district to the west, while Midtown’s party-hearty bros have invaded from the east and north. Property taxes and rents have both skyrocketed; despite the oil downturn, it’s almost impossible to find a one-bedroom for less than $800 a month. Having gained more acceptance from society at large, the LGBT community has scattered to neighborhoods like Westbury and Oak Forest. Bohemians have fled to the East End, Acres Homes, and Independence Heights — the gentrified Houston Heights no longer an option — or have left Houston altogether.” [Texas Monthly] Photo of house across from Menil Park, 1999: Alex Steffler, via Swamplot Flickr Pool [license]

Architectural details, building materials, windows, and flooring are now being picked from the the Midtown building at 1505 Hadley St. known as the Rice Mansion, a reader suggests. The photo sent above from this morning appears to show someone pulling boards from the threshold at the front door. The triple window fronting the building’s attic has already been yanked out.

Also removed from the property: a large amount of Destiny’s Child memorabilia — but that was last year, when the band’s former manager, Mathew Knowles, sold the entire block to the parent company of the neighboring Midtown Advantage BMW car dealership. The Rice Mansion served as the headquarters of Knowles’s Music World Entertainment for 15 years, and was considered the birthplace of the careers of his daughters, Beyoncé and Solange Knowles.

Another building on the property with a Destiny’s Child connection and a later stint as a wedding and event venue — the House of Deréon Media Center at 2204 Crawford St. — was torn down last month.

- Previously on Swamplot:How We Know Destiny’s Child Was Gone from the House of Déreon Before Its Demo; Comment of the Day: The Midtown Home of Destiny’s Child Has Met Its Destiny; If You Liked It Then You Shoulda Put a Bid On It: House of Deréon Gets Its Demo Permits; Daily Demolition Report: Final Destiny; Destiny’s Child Mural on House of Deréon Media Center Wins Midtown Demolition Staredown; Demo Equipment Is Now Waiting Patiently Outside the House of Deréon Media Center in Midtown

Photo: Swamplot inbox

COMMENT OF THE DAY RUNNER-UP: HOUSTON WOULD HAVE NO PART OF THE CONFEDERACY  “Where, exactly, is the intersection of Sam Houston and ‘confederate history’?

March 16, 1861 — Sam Houston refuses to take the oath of the confederacy:

‘Fellow citizens, in the name of your rights and liberties, which I believe have been trampled upon, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of the nationality of Texas, which has been betrayed by the Convention, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of the Constitution of Texas, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of my own conscience and manhood, which this Convention would degrade by dragging me before it, to pander to the malice of my enemies . . . I refuse to take this oath.’†[Diaspora, commenting on Best Buy’s Houston Warehouse Hunt; Sunrun Comes To Town; Is That Your Mermaid House Floating in the Gulf?] Photo of Sam Houston statue at Hermann Park: elnina, via Swamplot Flickr pool

“Where, exactly, is the intersection of Sam Houston and ‘confederate history’?

March 16, 1861 — Sam Houston refuses to take the oath of the confederacy:

‘Fellow citizens, in the name of your rights and liberties, which I believe have been trampled upon, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of the nationality of Texas, which has been betrayed by the Convention, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of the Constitution of Texas, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of my own conscience and manhood, which this Convention would degrade by dragging me before it, to pander to the malice of my enemies . . . I refuse to take this oath.’†[Diaspora, commenting on Best Buy’s Houston Warehouse Hunt; Sunrun Comes To Town; Is That Your Mermaid House Floating in the Gulf?] Photo of Sam Houston statue at Hermann Park: elnina, via Swamplot Flickr pool

COMMENTS OF THE DAY: WHEN HOUSTON JEWELRY WRAPPED A SHINY BAND AROUND A COUPLE OF DOWNTOWN BUILDINGS AT 720 RUSK  “We bought this building from Star Furniture in 1966 and operated in it until 1983 when we were offered a very generous price at the top of the market. After we left the building stayed empty until the Subway opened. . . . This is how the building looked when it was remodeled by architect Arnold Hendler in 1966.” [Rex Solomon, commenting on Downtown Houston Is Now Down To A Single Street-Level Subway] Photo: Houston Jewelry

“We bought this building from Star Furniture in 1966 and operated in it until 1983 when we were offered a very generous price at the top of the market. After we left the building stayed empty until the Subway opened. . . . This is how the building looked when it was remodeled by architect Arnold Hendler in 1966.” [Rex Solomon, commenting on Downtown Houston Is Now Down To A Single Street-Level Subway] Photo: Houston Jewelry

THE INVENTION OF UPPER KIRBY  Among Houston’s grids, strips, and cul de sacs, let a million neighborhoods bloom! Perhaps the story of how the area around upper Kirby Dr. came to be known as Upper Kirby can form some sort of template for this city’s vast numbers of undifferentiated districts just waiting to be branded? “We weren’t Greenway Plaza, we weren’t Montrose, we weren’t Rice Village,†Upper Kirby Management District deputy director Travis Younkin tells reporter Nicki Koetting. It was a section of town that lacked identity. “This nameless neighborhood, Koetting adds, “was the sort of place you drove through on the way to other, named neighborhoods.” One helpful step along the way: Planting the shopping areas with red phone booths. “The authentic British phone booths are an homage to Upper Kirby’s acronym, and actually operated as phone booths for a few decades until cellphones became the norm,” Koetting notes. “Now, the telephone booths are lit from within and locked, serving today as a visual indication to visitors that they’ve arrived in Houston’s own UK.” [Houstonia] Photo: WhisperToMe

Among Houston’s grids, strips, and cul de sacs, let a million neighborhoods bloom! Perhaps the story of how the area around upper Kirby Dr. came to be known as Upper Kirby can form some sort of template for this city’s vast numbers of undifferentiated districts just waiting to be branded? “We weren’t Greenway Plaza, we weren’t Montrose, we weren’t Rice Village,†Upper Kirby Management District deputy director Travis Younkin tells reporter Nicki Koetting. It was a section of town that lacked identity. “This nameless neighborhood, Koetting adds, “was the sort of place you drove through on the way to other, named neighborhoods.” One helpful step along the way: Planting the shopping areas with red phone booths. “The authentic British phone booths are an homage to Upper Kirby’s acronym, and actually operated as phone booths for a few decades until cellphones became the norm,” Koetting notes. “Now, the telephone booths are lit from within and locked, serving today as a visual indication to visitors that they’ve arrived in Houston’s own UK.” [Houstonia] Photo: WhisperToMe

COMMENT OF THE DAY: WHEN THEY RAISED GREAT GRANNY’S  “This house has some wonderful history. It was originally a one story that was raised up by cranes and the ground level story was built underneath. During WW One, they would roll up the rugs and host dances for the soldiers. It was the home of my great grandparents who lived there with their children when they moved from PA. My two spinster Great Aunts lived there all their lives. It broke the hearts of the family when it had to be sold but no one had the means to buy and restore it. I wanted to share for those of you that had posted the kind comments.” [Renee Lauckner, commenting on Corner Lot Hidden Away for Decades Beneath 1904 Heights House Could Join the Commercial Crowd] Photo: Swamplot inbox

“This house has some wonderful history. It was originally a one story that was raised up by cranes and the ground level story was built underneath. During WW One, they would roll up the rugs and host dances for the soldiers. It was the home of my great grandparents who lived there with their children when they moved from PA. My two spinster Great Aunts lived there all their lives. It broke the hearts of the family when it had to be sold but no one had the means to buy and restore it. I wanted to share for those of you that had posted the kind comments.” [Renee Lauckner, commenting on Corner Lot Hidden Away for Decades Beneath 1904 Heights House Could Join the Commercial Crowd] Photo: Swamplot inbox

WESLAYAN’S CRUEL TWIST SLAYS  Reader Adam Goss, who identifies himself as a Houstonian — and a graduate of Wesleyan University in Connecticut — writes that it “drives him insane” that “the street named after our alma mater is misspelled. All the surrounding streets are named after similar universities and colleges (Amherst, Oberlin, Georgetown), yet for some reason the largest of all, Weslayan, is spelled incorrectly.

How would Rice grads like it if a major thoroughfare in Chicago was named after the famed Houston university, Rize Avenue. Or if Boston named a major street Longhornes, after a famed UT alum?”

Photo of street sign at the corner of Weslayan and W. Alabama St.: Jeremy Hughes

Reader Adam Goss, who identifies himself as a Houstonian — and a graduate of Wesleyan University in Connecticut — writes that it “drives him insane” that “the street named after our alma mater is misspelled. All the surrounding streets are named after similar universities and colleges (Amherst, Oberlin, Georgetown), yet for some reason the largest of all, Weslayan, is spelled incorrectly.

How would Rice grads like it if a major thoroughfare in Chicago was named after the famed Houston university, Rize Avenue. Or if Boston named a major street Longhornes, after a famed UT alum?”

Photo of street sign at the corner of Weslayan and W. Alabama St.: Jeremy Hughes