ALL THE DAMS AND MAGIC WETLANDS CAN DO  Big, fat, cleared floodplains are the best way to handle a very large storm, explains wetlands scientist John Jacob — because nothing else is going to: “An average rainfall of 35 inches over all of Harris County (Harvey) is just over 1 trillion gallons. At most, there are about 50 billion gallons of stormwater detention capacity in Harris County wetlands (no one has measured this — I had to make some very broad assumptions). So that means that the wetlands at best could handle about 5% of the total volume of Harvey rainfall. In the large scheme of things, it’s not much. And the scheme of things in Harvey is indeed very large.

So much for the magic wetlands. But what about our engineered drainage system? I calculate a somewhat larger detention capacity — between our large US Army Corps of Engineers Katy Prairie reservoirs (~400,000 acre-ft) and Harris County Flood Control District detention (about 34,000 acre-feet), we have about 130 billion gallons of detention volume. More than what we have for wetlands, but still only about 14% of Harvey. As we painfully saw, also overwhelmed.

And what of green stormwater infrastructure — rain gardens, bioswales, green roofs, etc.? We don’t have any good numbers here, but you can be sure that even if these practices were widespread, the volume would be very small relative to wetlands and detention basins. These practices are designed to capture at best a 2 inch storm.” [Watershed Texas] Photo of Willow Waterhole Greenspace: Luz (license)

Big, fat, cleared floodplains are the best way to handle a very large storm, explains wetlands scientist John Jacob — because nothing else is going to: “An average rainfall of 35 inches over all of Harris County (Harvey) is just over 1 trillion gallons. At most, there are about 50 billion gallons of stormwater detention capacity in Harris County wetlands (no one has measured this — I had to make some very broad assumptions). So that means that the wetlands at best could handle about 5% of the total volume of Harvey rainfall. In the large scheme of things, it’s not much. And the scheme of things in Harvey is indeed very large.

So much for the magic wetlands. But what about our engineered drainage system? I calculate a somewhat larger detention capacity — between our large US Army Corps of Engineers Katy Prairie reservoirs (~400,000 acre-ft) and Harris County Flood Control District detention (about 34,000 acre-feet), we have about 130 billion gallons of detention volume. More than what we have for wetlands, but still only about 14% of Harvey. As we painfully saw, also overwhelmed.

And what of green stormwater infrastructure — rain gardens, bioswales, green roofs, etc.? We don’t have any good numbers here, but you can be sure that even if these practices were widespread, the volume would be very small relative to wetlands and detention basins. These practices are designed to capture at best a 2 inch storm.” [Watershed Texas] Photo of Willow Waterhole Greenspace: Luz (license)

Tag: Wetlands

WHERE HIGHWAY 87 CRUMBLED BEFORE THE TIDE  The part of Texas “[where] storms are what you talk about” is the subject of John Nova Lomax’s dispatch this week in Texas Monthly — more specifically, the 16-mile stretch of coast where the state gave up on rebuilding SH 87 after the last of a series of hurricane washouts in the 1980s. Amid nude beach signage, dolphin carcasses, and the rusting remains of pipelines and 4-wheelers, Lomax meditates on the idea that the battered stretch of coast, where Texas’s beaches and barrier islands begin dissolve away into a Louisiana-style tangle of eroding wetlands, “once functioned as a seawall: there was a natural ridgeline made of shells and sand that was used as a trail by Native Americans, then Spaniards, then Texans. Then the ridge was bulldozed and repurposed to grade Highway 87, the road that no longer exists — and the one bulwark against the sea was gone.” [Texas Monthly] Photo of eroding highway in McFaddin National Wildlife Refuge: US Fish and Wildlife Service

The part of Texas “[where] storms are what you talk about” is the subject of John Nova Lomax’s dispatch this week in Texas Monthly — more specifically, the 16-mile stretch of coast where the state gave up on rebuilding SH 87 after the last of a series of hurricane washouts in the 1980s. Amid nude beach signage, dolphin carcasses, and the rusting remains of pipelines and 4-wheelers, Lomax meditates on the idea that the battered stretch of coast, where Texas’s beaches and barrier islands begin dissolve away into a Louisiana-style tangle of eroding wetlands, “once functioned as a seawall: there was a natural ridgeline made of shells and sand that was used as a trail by Native Americans, then Spaniards, then Texans. Then the ridge was bulldozed and repurposed to grade Highway 87, the road that no longer exists — and the one bulwark against the sea was gone.” [Texas Monthly] Photo of eroding highway in McFaddin National Wildlife Refuge: US Fish and Wildlife Service

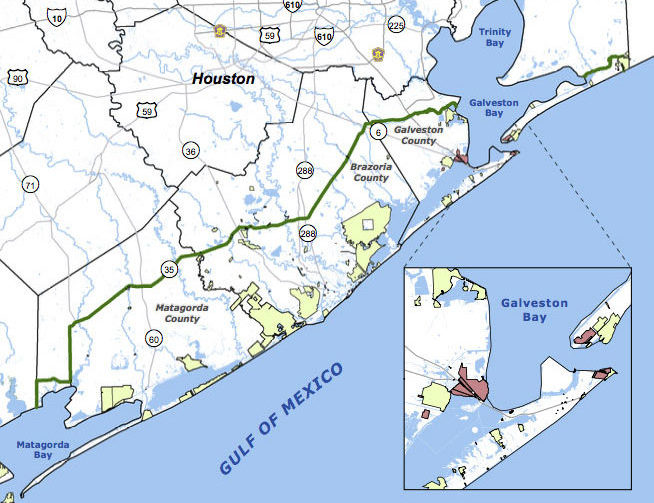

SCENIC UPPER TEXAS COASTAL SWAMPS, BEACHES, PLANTATIONS A LITTLE CLOSER TO GOING NATIONAL  Jefferson County’s commissioners are the latest to give a formal thumbs up to a proposal for the Lone Star Coastal National Recreation Area, which would bundle together a patchwork of parks, historical sites, and variously refinery adjacent nature preserves from the Bolivar peninsula down to Matagorda Bay. The concept for a regional rec zone was developed shortly after Hurricane Ike’s big splash on the Texas coast in 2008: researchers noticed that some of those larger patches of undeveloped wetlands helped buffer storm surge damage, and started looking at whether keeping them around could be profitable in other ways. No new land would be scooped up for inclusion in the 4-county zone, unless it were offered voluntarily — but the whole region would be marketed under the National Parks Service’s banner as a package to birdwatchers, beachgoers, Strand-walkers, and the like. The proposed area would still need some level of National Parks Service staff, and approval from Congress — which is currently considering major cuts to the Department of the Interior’s budget. [Beaumont Enterprise; Houston Chronicle] Map of proposed Lone Star Coastal National Recreation Area: LSCNRAÂ

Jefferson County’s commissioners are the latest to give a formal thumbs up to a proposal for the Lone Star Coastal National Recreation Area, which would bundle together a patchwork of parks, historical sites, and variously refinery adjacent nature preserves from the Bolivar peninsula down to Matagorda Bay. The concept for a regional rec zone was developed shortly after Hurricane Ike’s big splash on the Texas coast in 2008: researchers noticed that some of those larger patches of undeveloped wetlands helped buffer storm surge damage, and started looking at whether keeping them around could be profitable in other ways. No new land would be scooped up for inclusion in the 4-county zone, unless it were offered voluntarily — but the whole region would be marketed under the National Parks Service’s banner as a package to birdwatchers, beachgoers, Strand-walkers, and the like. The proposed area would still need some level of National Parks Service staff, and approval from Congress — which is currently considering major cuts to the Department of the Interior’s budget. [Beaumont Enterprise; Houston Chronicle] Map of proposed Lone Star Coastal National Recreation Area: LSCNRAÂ

A through-the-curtains peek at at the reassembly of about 2,500 sq. ft. of miniaturized Texas landscape (made by T W Trainworx for the Houston Museum of Natural Science’s soon-to-open model train exhibit) comes from a reader who snuck a glance on Thursday. The exhibit, which should open some time after the 2nd week of installation wraps up, looks like it’ll include hand-carved models of some of Texas’s less flat geographies, including the Balcones Escarpment and Texas’s own pretty darn grand canyon, Palo Duro. The official details on opening and closing dates aren’t out yet, but a behind-the-scenes event description on the museum’s website notes that the exhibit will also show off some more familiar Gulf Coast features like “oil country salt domes, prairies and wetlands.” Natural stone landmarks, like Enchanted Rock, and unnatural stone monuments, like the state capitol, will also be part of the display.

Photo: Swamplot inbox

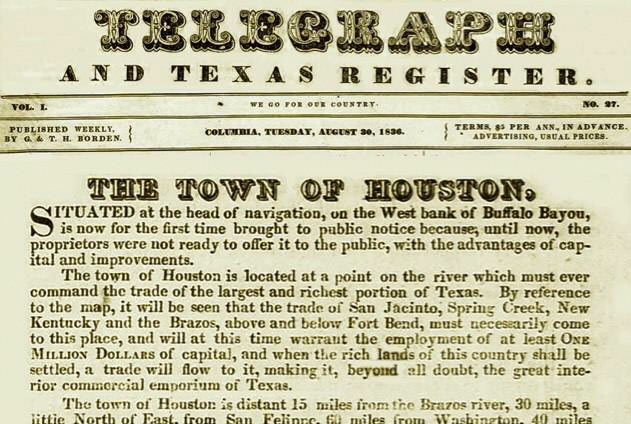

It’s that time again — Houston’s birthday celebration, observed traditionally on the anniversary of the publication of the Allen brothers’ newspaper ads offering land for sale in the area in 1836. Among the more eyebrow-worthy claims put forward by the founders: that the “beautifully-elevated” area (depicted nestled amid a clutch of towering hills) was already the site of regular steamboat traffic (the Laura wouldn’t make the first steamboat run up the sandy twists of Buffalo Bayou to Allen’s Landing until the following year), and that the area “[enjoys] the sea breeze in all its freshness” and is “well-watered” (that part, at least, is likely undisputed).

The ad text also claims that “Nature appears to have designated this place for the future seat of Government,” though Lisa Gray suggests this morning that a few well-timed gifts to members of the newly-minted Texas Legislature may have been responsible as well. Gray writes that the city hosted the Texas government from 1837 until the legislators, tired of the heat and mosquitoes, voted to move elsewhere in 1839.

Here’s the ad in its entirety, as it appeared 180 years ago today in the Telegraph and Texas Register:

NATIONAL GUARD TO DEPLOY DISCARDED CHRISTMAS TREES TO RESTORE LOUISIANA WETLANDS Meanwhile, in New Orleans:Â The US Fish and Wildlife Service, along with the Louisiana National Guard’s 1st Assault Helicopter Battalion, will conduct the city’s annual Christmas Tree Drop, in which thousands of fir trees collected this week will be deposited by Black Hawk into the 23,000-ac swamp that sits within the city limits. The dead trees placed in the Bayou Sauvage National Wildlife Refuge allow sediment to collect and provide habitat, creating a base for recolonization of degraded wetland areas by native marsh grasses and birds; about 175 acres of wetlands have been restored in this way since the program began. [The Times-Picayune, Mother Nature Network]

COMMENT OF THE DAY: IS HOUSTON ALREADY EQUIPPED FOR EXTRATERRESTRIAL SPRAWL?  “What a waste! The coastal prairies will soon be gone and few will remember them. Everyone will say, ‘Well, Houston doesn’t have much in the way of natural environment anyway, but at least it has affordable housing compared to a lot of cities,’ and ‘Oh yeah, it is hot, but we stay inside most of the time, so who cares about the outside world?’ Maybe Houstonians should be the first to move to Mars or the Moon. (Hopefully) there aren’t any irreplaceable ecosystems to replace with big box stores, suburban homes, and highways!” [Duston, commenting on Houston Shifting to a Buyer’s Market; Making Way for the Lancaster Hotel Parking Lot] Illustration: Lulu

“What a waste! The coastal prairies will soon be gone and few will remember them. Everyone will say, ‘Well, Houston doesn’t have much in the way of natural environment anyway, but at least it has affordable housing compared to a lot of cities,’ and ‘Oh yeah, it is hot, but we stay inside most of the time, so who cares about the outside world?’ Maybe Houstonians should be the first to move to Mars or the Moon. (Hopefully) there aren’t any irreplaceable ecosystems to replace with big box stores, suburban homes, and highways!” [Duston, commenting on Houston Shifting to a Buyer’s Market; Making Way for the Lancaster Hotel Parking Lot] Illustration: Lulu

Here’s some raw footage from a camera-wielding drone flight landscape artist and researcher Steve Rowell piloted earlier this year over portions of the Baytown Nature Center, the Crystal, Scott, and Burnet Bay peninsula that not too long ago was the home of the tony Brownwood subdivision — before it got all sinky and decided to subside 10 or so feet into the water. In some portions of the video, you can still spot the occasional home or garage slab from a fifties- or sixties-era rancher or 2, not to mention concrete broken up from other foundations and driveways and recycled on-site into surge barriers that now control the more recent, court-ordered wetlands environment.

Drought has turned land that used to be part of Lake Houston into a jungle of 14-ft.-tall snake-infested weeds. Waterfront residents of Kings River Village, near the northern end of the lake in Humble, would like to knock down the vegetation that’s sprung up as the lake has receded, and that now surrounds their newly dry backyard docks. But some are proceeding with caution because they don’t own the newfound land and are wary of legal and ecological issues that might result from clear-cutting the newly exposed wetlands. “Right now, we are just in a situation where our kids can’t go back anywhere near the lake because of the weeds and the snakes that are back there,” Clear Sky Dr. resident David Labbe tells the Lake Houston Observer. “We’ve seen an abundance of snakes. We don’t know what rights we have, as homeowners, to go out there and try to remedy the situation.†Labbe has contacted the Army Corps of Engineers, the San Jacinto River Authority, and Houston officials, but hasn’t received an answer yet.

- Lakefront residents seek permission to solve growing drought-induced problem [Lake Houston Observer]

TRYING TO PRESERVE PRESERVE LAND A year and a half after Hurricane Ike, what’s going on with Marquette Investments’ “The Preserve at West Beach” development plan for a huge chunk of Galveston’s West End? Here’s an update on a piece of it: “Last year, the environmental group Artist Boat applied for $11 million in federal Hazard Mitigation Grant Program money to buy 343 acres of bay-front land from developer Marquette Land Investments. Gov. Rick Perry rejected the application, even though island leaders and environmentalists flooded his office with e-mails, letters and faxes urging him to save one of the island’s most ecologically diverse tracts. . . . Now, Artist Boat and the city of Galveston are working together to secure a $3 million Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Program grant, administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association. The grant application was submitted Thursday. . . . [Artist Boat Executive Director Karla]Klay said the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association will announce the winners of the grant within six to nine months. Darren Sloniger and his partners at Marquette agreed to provide $3 million in matching land value if Klay and the city get the grant. If that happens, the city would hold the title to one-third of the 343-acre site, which sits east of 11 Mile Road and north of Settegast Road. Marquette intended to turn the site into a 35-acre marina and residential subdivision. The property is part of a 1,058-acre development that will include a 15-story resort hotel, 4,000 condominiums and houses and an 18-hole golf course.” [Galveston County Daily News]